Sometimes in geography it is necessary to know which objects are close to other objects. In MongoDB, one can select a feature which is near a certain point. From what I can gather, datatypes other than “Point” are not yet supported.

This is done in MongoDB by using the $near function which takes the parameters $geometry, $minDistance, and $maxDistance.

Say that we want to find all features in the ParisCollection collection which are between 1 and 5 kilometers of the Eiffel Tower, we would write the following query.

db.ParisCollection.find(

{

location:

{ $near :

{

$geometry: { type: "Point", coordinates:[48.858532, 2.294395]},

$minDistance: 1000,

$maxDistance: 5000

}

}

}

)

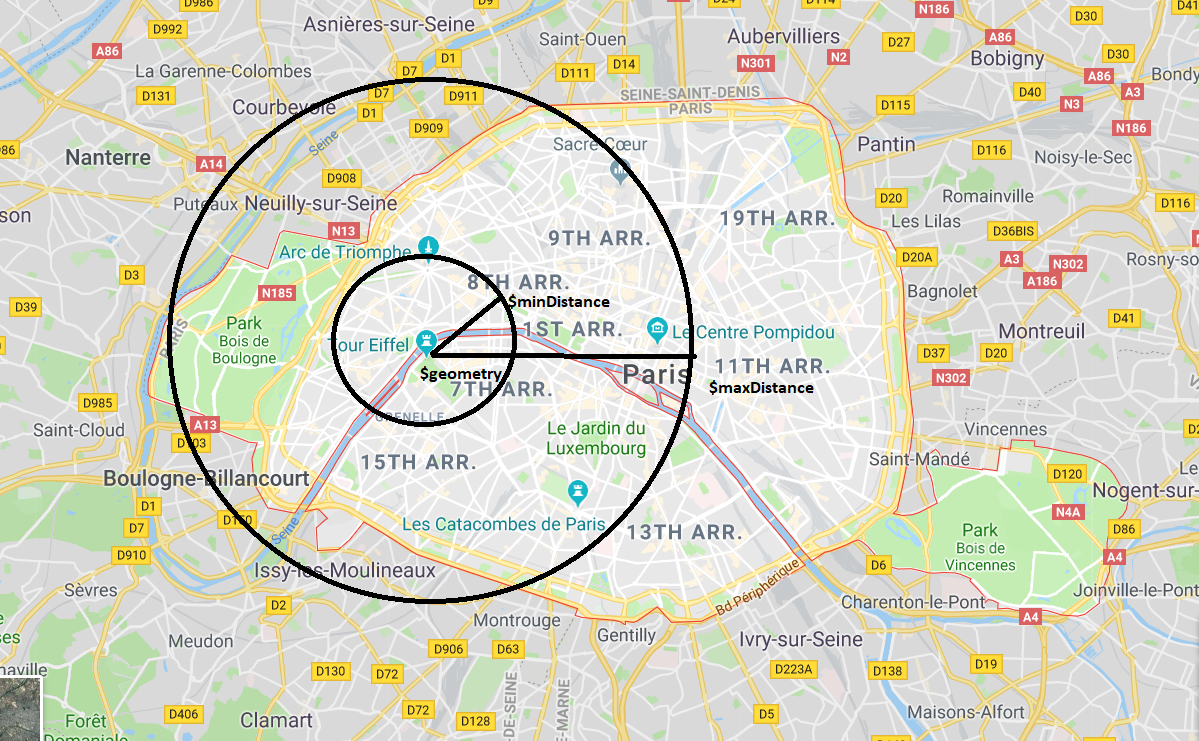

Here is a visual representation of what we are currently doing:

As you can see, the $geometry variable is a Point which coordinates are exactly where the Eiffel Tower is. $minDistance and $maxDistance variables specify two circles around the center point. Everything feature which exists in the ParisCollection and has a geometry which lies between these two distances will be returned by the above query.